UC Berkeley: The mystery behind California's high gas prices

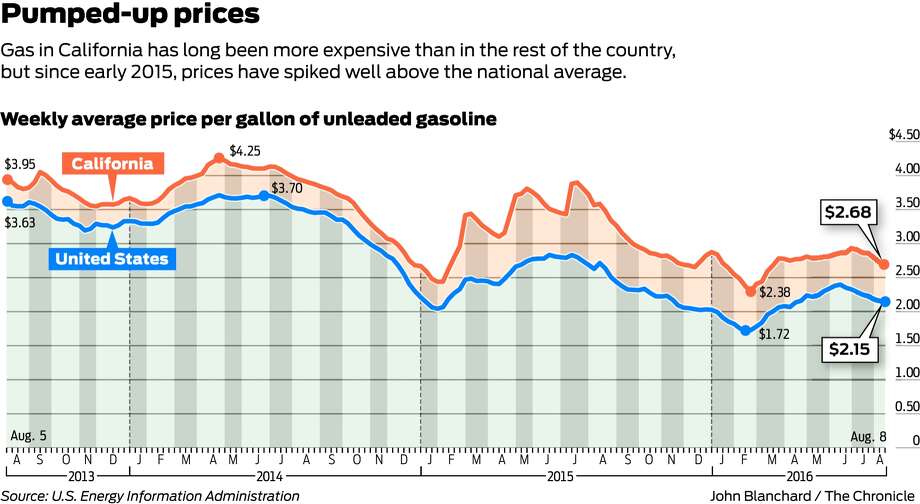

California routinely has some of the highest pump prices in the United States, the result of high taxes and the use of a pollution-reducing gasoline formula not sold elsewhere. But the premium we pay historically hovered between 25 and 35 cents per gallon. Relatively new expenses related to California’s fight against global warming have added about 15 cents to that premium, but it can’t explain the elevated prices that have persisted for 18 months.

By one estimate, the unusually wide gap between California’s gasoline prices and the national average has cost the state’s drivers more than \\$10 billion.

A panel of fuel-market experts convened by the state government has tried for months to pinpoint causes for the high prices. It will meet again Tuesday.

But despite exploring a number of possible answers, including the role and pricing power of refineries, the panel’s chairman says he and his colleagues may not be able to prove any of them. Doing so, he said, would likely require far greater legal authority than the panel has.

“We have no subpoena power, we have no investigative power — all we can do is ask people to come talk to us,” said UC Berkeley energy economist Severin Borenstein, chairman of the state’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee. “If someone is going to really dig in, it’s going to take more power.”

California Attorney General Kamala Harris has a representative on the committee, and in June, her office reportedly issued subpoenas to several oil companies, seeking information on gasoline supplies and pricing. (A spokesman for the attorney general declined to comment.)

But her office has investigated California’s gasoline market before and come away empty-handed. And Borenstein fears that most state officials are ignoring the problem.

“There seems to be almost no interest among policy makers, and the reason is that prices are low,” he said. “Given that we’re talking about billions of dollars, I think it’d be a good idea for California to make a bigger effort to find out going on.”

The Western States Petroleum Association did not respond to a request for comment by deadline.

Even in the best of circumstances, Californians pay more for gasoline than most Americans.

Taxes on gasoline in the Golden State tend to be among the country’s highest. Federal, state and local taxes and fees add more than 50 cents per gallon for California drivers, according to the American Petroleum Institute — 9 cents more than the national average.

The state’s “cap and trade” system for reining in the greenhouse gases behind climate change tacks on another 11 cents. A regulation that requires oil companies to lower the “carbon intensity” of the fuels they sell in California adds an estimated 4 cents. The California Energy Commission includes both expenses and several others under “distribution and marketing” (see accompanying graphic).

But the state also suffers from having a market largely cut off from outside suppliers.

California uses its own gasoline blends, designed to fight air pollution. Other states use different blends, so most of California’s fuel comes from refineries located within the state.

If mechanical problems hobble one or more of those refineries, bringing in extra supplies from outside the state can take weeks. No pipelines connect California to the refineries on the Gulf Coast, so any imports must come by ship, traveling either from Asia or through the Panama Canal.

In February 2015, part of a Los Angeles County refinery then-owned by ExxonMobil exploded, and did not return to normal operations until May of this year. Gasoline prices jumped after the explosion, eventually hitting \\$3.44 for a gallon of regular, according to GasBuddy.com. The national average, in contrast, was \\$2.46.

But in the months that followed the explosion, the difference between California’s prices and the national average never returned to normal, even though the price spike from a refinery outage is expected to be short-lived due to requirements that the refinery owner find alternative supply to fulfill its contracts. At one point in mid-July, 2015, the state’s average for regular reached \\$3.89, at a time when the country on average was paying \\$2.77.

Rather than rising to meet the occasion, gasoline imports to the state slowed dramatically in July and August. Oil industry representatives later told the Petroleum Market Advisory Committee that there had been a shortage of U.S.-flagged ships available to bring fuel from the gulf to California. A nearly century-old federal law requires that only U.S.-flagged ships can ferry cargo from one U.S. port to another.

In addition, since making and shipping the fuel can take weeks, traders were hesitant to bring in gasoline tankers for fear that the price premium would shrink by the time the ships arrived.

The advocacy group Consumer Watchdog calls those explanations excuses. The oil industry, its says, was deliberately starving the state of gasoline to keep prices high. The group even cited a U.S.-flagged tanker that ExxonMobil had parked in Singapore for two months during the height of the price spike. The ship eventually sailed to Los Angeles with a cargo of fuel but didn’t unload it, taking it to Florida instead.

ExxonMobil replied that the ship had been undergoing maintenance at a Singapore dry dock.

“The fundamental problem is we’ve got too much market power in too few hands,” said Jamie Court, Consumer Watchdog’s president. “Four refiners control 80 percent of the market. ... That creates the ability to artificially reduce supply and artificially inflate prices.”

Court’s group also said the oil companies charged significantly higher wholesale prices to owners of branded gas stations than the prices the same companies charge to independent stations. Gas stations affiliated with a specific brand must, by contract, buy their wholesale gasoline from that brand.

Borenstein isn’t convinced that the oil companies have tried to starve the California market of gasoline. He points to Exxon in particular, noting that the Torrance refinery — which the company has since sold — was the company’s only refinery in California. While repairs were under way, Exxon had to buy replacement fuel to fulfill the refinery’s supply contracts — meaning the company had to pay elevated prices itself.

“The view that, ‘Oh, this is just a logistical problem,’ or the view that the major players are exercising market power to keep prices up — neither has been really born out,” he said.

Комментарии